Pullsaws were developed by the Japanese to suit their style of woodworking (sitting cross-legged on the floor with the workpiece in front of them). The teeth of the blade point towards the handle instead of away from it, so the actual cutting happens as you pull the saw towards you rather than as you push it away.

A Western-style saw cuts as you push it so always tries to buckle as you push into the wood: so even if it has a back like a tenon saw it cannot be very thin. A pullsaw is constantly tensioned by the workpiece as you pull it through, so the blade can be very thin. The thinnest saws I sell have a blade which is only 300 microns thick (that is 0.3 millimetres) and they therefore have to work far less hard to cut the timber.

With a pullsaw the blade tensions itself as it is pulled and can therefore be much thinner, meaning a much easier, smoother cut requiring less effort, producing much less sawdust, and leaving a very smooth cut edge. You therefore get a better finish and less mess for less work: a winning combination in my view! The vast majority of people I meet at shows who try a pullsaw agree that they are far easier and smoother to use than Western saws.

The best blade for any job depends on several factors:

A universal saw is designed to be able to cut the wood in any direction, but does not cut with or across the grain quite as easily or efficiently as a purpose-made ripsaw or crosscut saw. A universal saw would cope with a project like cutting 6-foot beams in half lengthwise, but a ripsaw would be far quicker and easier. If you then had to cut the narrow beams into lots of shorter pieces a crosscut saw would be easier than the universal (although the difference here is not so great). Basically what I am saying is that if you had to do something like that once, a universal saw would be fine but if you were doing it regularly you would find it much easier to to use a ripsaw and then a crosscut saw.

You are absolutely right that cutting dovetails usually involves rip- and slant-cutting. Dozuki blades are essentially crosscut, but the difference between crosscut and universal blurs into insignificance when you get into the ultra-fine teeth like these.

I'm afraid I don't actually have a dedicated hardwood ripsaw as yet. Some time ago I sent a 50 kilo section of oak to the factory for development testing, as customers had given me feedback that the standard ripsaws can lose set and follow the grain rather than the cutting line when working extensively in oak and similar hardwoods. The Z-saw factory had no experience of such a dense timber (Japanese hardwoods are much lighter) and planned to develop a suitable saw or saws. Everything changed with the retirement of the previous CEO, as his successors do not seem interested in any new development unless it is likely to lead to volume sales. I have asked again, however.

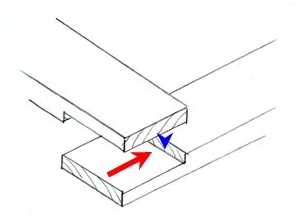

I presume your husband needs the ripsaw for the cut shown here with

the red arrow, and a crosscut saw for the shorter cut with the blue

arrow.

If your paintings are not huge I would have thought

that any of the ripsaws I sell would do the job: the H-300 has a 12"

blade and the other 2 have 10" blades so are by no means too small for

the job. The saw with the double-edged

blade would also save your husband changing saws for the

second cut, although the double-edged saw would not be my

first choice largely from a safety perspective. These are

very sharp saws, "scary sharp" according to one customer,

and I am not overly keen on the idea of using a saw blade

with another set of teeth upward.

I know exactly what you mean: I get a bit

out of breath trying to blow sawdust away! The same problem occurs

with jigsaws, which also cut on the upstroke.

In terms of technique I haven't found the

perfect solution yet: with some materials putting a piece of scrap

timber under one end of the workpiece gives enough of a slope for

most of the dust to fall away from the line, but care is needed to

cut away from the vertical. I have also on occasion used a blade

with no set to the teeth and held this against a straightedge.

There is an option, however, which you might

want to consider for the future, and it involves a metal straightedge. I sell saw guides which are absolutely brilliant for cutting straight and at the correct angle.

A number of videos are available showing, amongst other things, how to cut wide boards using a straightedge clamped to the workpiece to guide the saw guide. You can see them here.

You are not being a pain at all: happy to answer questions. As far as tear out is concerned let me reassure you that I have never found this to be a problem as the thin blades of pullsaws do not seem to tear in the same way as thicker Western-style blades. I have never had this complaint from any other customer either.

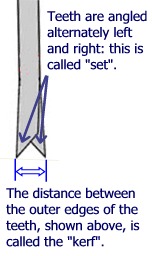

Set describes how some of the teeth on a blade are angled ("set") very slightly to the

left while others are angled the same amount to the right.

Kerf is a way of measuring the effective thickness of a blade at the tips of the teeth, and is the

same as the width of cut that the blade will make. For the vast majority of saw blades the kerf will be slightly

greater than the actual blade thickness.

You are correct that these saws are very light, and the handles are generally easier to grip for smaller hands. I have had a lot of very positive feedback from ladies who have tried my saws at shows.

I honestly hadn't noticed this myself so I asked the factory. Their reply said: "We have been applying “non-electrode Ni-P plating” on some of our saw blades for rust prevention. The blue tint is removed when blades are Ni-P plated. This is the reason why the Hard Impulse blue tint has vanished. The hardness on saw tip is still around Hv 900 as a matter of course."

Copyright © Woodwork Projects